1 : Of Spies & Rogues

2 : He is with you... 3 : The Great Buddhas 4 : Recollections 5 : A Broken Peace 6 : The Salt of the Earth 7 : With Friends Like This 8 : An Ill Wind 9 : What the Devil... 10 : Not by Bread Alone 11 : A Loss of Face 12 : The Water of Life 13 : Shades of Mercy 14 : Afterword Appendix

Buy the book from Amazon Buy the book from Amazon45 color photographs, several sketches, and 3 maps. The Spy of the Heart can also be ordered direct from the author : Send a check for $20 to Real Impressions, P.O. Box 714, Sausalito, CA 94966, USA. incl. Postage & Packaging.

|

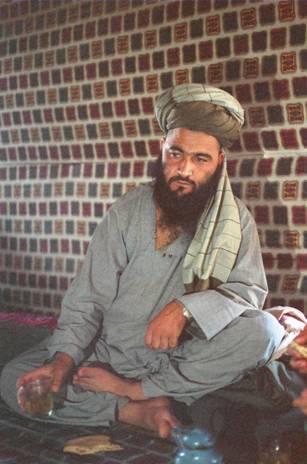

He who knows himself, knows his Lord. The Prophet Muhammad (Upon him peace) 1. Of Spies and Rogues“Tell us who you are, brother,” he said, pointing an AK-47 directly at my chest. I had been stopped at a Hesbi Islamic checkpoint; uncertainty started to set in. My years of Persian and my completely native dress and look, even my story of coming from a northern Afghan village, whose people I resemble most, didn’t ensure an uneventful passage here at Tangi Boom in central Afghanistan. The man pointing the gun at me was with Hesbi Islami, the resistance organization headed by the infamous Gulbudin Hekmatyar and made up, for the most part, of Pushtun fighters. They controlled the key checkpoint for this particular route into Afghanistan. The credentials that I carried were from their arch-rival, Jamiat Islami, commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud, and dominated by ethnic Tajiks. “Alright,” I answered, “I’m French. I’m traveling to the northern part of the country to help the needy.” It was true that I had spent my childhood in French Polynesia. As a precaution I always told strangers that I was French. Since the Islamic Revolution in neighboring Iran and as Afghans began to see that the United States was manipulating the war to its own advantage, it had become dangerous to be known here as an American. “Get into the jeep,” he pointed with the rifle. The four Afghans I had been traveling with had so far remained silent. Suddenly Abdul Hayy, the youngest, spoke up. “Please, Sikandar is a good man, a man who is helping our people!” Abdul Hayy used my local name, Sikandar, which had been given to me by Afghans because it rhymed with my last name, Darr. “Oh? You get in too,” the man ordered him. We sat in silence in the back seat and held on as the jeep lurched from side to side along the bumpy road to headquarters at Chak Wardak, about fifteen minutes away. Immediately after we arrived, Abdul Hayy and I were separated and I was taken into a small dark room that smelled of fresh mud. In the dim light I could make out strands of straw mixed in with the mud between the sun-dried earthen bricks that formed the wall. The ceiling was a soft ivory web of rustic tree trunks crossed by branches and leaves supporting a mud roof. I tried to still my imagination, now visualizing various unpalatable scenarios of what was likely to happen next. My Hesbi Islami captors were notorious for kidnappings. They were feared for holding enemies and rivals captive for long periods, and even for murder and summary execution. “Oh God help me! Be brave, be calm. Be brave, be calm,” I repeated within. A stocky man with a pock-marked face soon entered the room. He scowled, demanding, “Who are you? What are you doing in our country?” He was almost shouting. I started to explain my work, that there were many thousands of internally displaced refugees who needed help and . . . “Who gave you permission for this?” he demanded. I pulled credentials from a vest pocket, a letter from the main office of Jamiat Islami in Peshawar, Pakistan and handed this to him. He read it, still scowling, and quickly threw it aside. “You have no permission to be here! You are a spy!” “Please,” I begged, “I’m not a spy! I’m here to do work with the needy. Why do you not accept my letter?” “Jamiat has no authority in Afghanistan,” he replied angrily. “You have no permission to be here!” He got up and left the room stiffly. “Be brave, be calm. Be brave, be calm,” I breathed. The hushed conversation of the guards at the door penetrated the silence of my worry. The thought of escape crossed my mind. There was a small window at one end of the room. “Is it big enough to get through? Maybe if I twist my shoulders diagonally,” I thought. Something inside told me not to try it. “No. Wait. Just wait,” I said to myself. Meanwhile, I thought about how crazy my situation was. Why had I come to Afghanistan in the first place? “Okay,” I mentally berated the adventurous part of myself, “so you came here to learn more about the culture and you wanted to help the needy. You wanted to study the literature and spirituality of Afghanistan. You were curious about Islam. Now look where you are! In the hands of fanatics who will do with you whatever they please!” I was thirty-eight years old. I had grown up in California’s tolerant, multi-cultural environment where I made friends over the years with immigrants from the Islamic world. I was drawn through these warm friendships to explore the richness of Islamic culture—the various arts from that part of the world drew me deeper, into a study of the ideas they represented. But it was with a romanticized ideal of the culture and people that I eventually traveled to the region. Little did I know what I was really getting into. I sat for an hour or so until another man entered the room. He was calm and poker-faced; he just sat there for a while studying me. Then with a manner of authority and firmness he asked, “Who are you, brother?” “I’ve been trying to explain, I’m a Frenchman working with internal refugees. I was just on my way to . . . ” “Why did you lie?” he interrupted me. “Why did you lie at the checkpoint? If you were an aid worker you wouldn’t have needed to lie!” His voice had raised a notch. “Yes, I lied,” I admitted. “But you know how hard it is to go through all the checkpoints in this country.” “And you have disguised yourself as an Afghan! What are you really up to, brother? Who are you working for?” “Please, I said what I did only to avoid being stopped. Please check my credentials. Please check my story.” He peered at my letter from Jamiat Islami and said, scoffing, “These people have no authority in Afghanistan. They are puppets of the West. Many of them are Maoists!” His attitude was one I often encountered in the years I worked in Afghanistan. Every tribal group, military organization, and ethnicity was contemptuous and dismissive of the rest. “Where is your passport?” he demanded. “It’s in Peshawar, I never carry it with me . . . ” “So you’ve been here before?” he queried, narrowing his eyes. “Well, yes, a few times into Konar and other border provinces. We have projects in Pakistan as well.” “You are lying. You are a spy!” he insisted again as he got up. He gave me a dismissive glance as he left the room clutching my letter from Jamiat Islami. I sat there feeling devastated, but oddly calm. I prayed again, and asked God for intervention. I thought about who might be able to help me from across the border in Pakistan, only a day or two away. My interrogator came back a couple of hours later. This time he started with, “I am Commander Asif, general commander of this area. You must tell me the truth. I don’t have much time to spend with you.” We went through an almost exact replay of our earlier conversation. He still wasn’t convinced by my story. “You will be imprisoned here until you tell me what your real mission is,” he announced. My heart sank at the thought of being held there, unable to get to friends and help; what I knew about Hesbi Islami’s treatment of spies, real or imagined, only made me more anxious. But I was also relieved that he was only threatening me with imprisonment. I had already imagined a more disturbing scenario, oddly with complete detachment. I had pictured being taken outside into the courtyard and suddenly shot to death. But now there was hope. I was sure the matter could be cleared up once they checked with their Peshawar office to see who I was—as long as they didn’t check too closely. If they found out I was an American I would be caught in another lie, one which would seem to confirm Commander Asif’s suspicions. The whole population seemed obsessed with the idea that foreigners, especially Americans, were spies. The irony is that the United States was funding this group of fanatics, though most Americans were completely unaware of it at the time. Hesbi Islami was a ruthless military machine, and for this reason, they were the ideal choice of both the CIA and the notorious ISI, Pakistani military intelligence. The CIA’s game was simple enough: humiliate the Soviet Union militarily and destroy the Marxist regime in Afghanistan. The ISI’s agenda was far more complex. They wanted to manipulate the political future of Afghanistan, possibly even absorb it into Pakistan, and they certainly wanted to control its politics and natural resources in the decades ahead. The ISI’s upper echelon included many Pushtun officers. Their hereditary tribal lands stretched—nearly—from Iran to the Indus River in northern Pakistan. As noted earlier, the role of ethnicity is one of the most important things that I came to understand during the years I worked in Afghanistan—ethnicity comes first. It comes before political, national, and even sectarian identity. It was therefore no surprise to me that the Pushtuns were working actively in Pakistani intelligence and closely with Hesbi Islami. Most Westerners favored the more moderate Jamiat Islami, largely out of admiration for its charismatic military leader, Ahmad Shah Massoud, the ‘Lion of Panshir.’ The moderate, inclusive vision that he articulated for Afghanistan’s future appealed to Westerners. Massoud was familiar with both traditional Islamic and modern Western thought. He had representatives in Europe and he worked closely with Western aid workers and journalists. He should have been more actively supported by the United States, but Pakistani intelligence had other plans. They despised Massoud because he was defiantly independent and wanted nothing of Pakistani intervention in Afghanistan. More importantly, Massoud was ethnically Tajik, of the main Persian-speaking population of Afghanistan. Pakistani intelligence wanted a Pushtun organization to dominate the Afghan resistance and the Pakistanis strongly influenced the distribution of American military aid, worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year, in the region. In the dark, hot room I waited, long minutes of self-awareness passed slowly. I fretted over my situation and my inauspicious affiliations. I was an American posing as a Frenchman posing as a northern Afghan of a rival ethnicity with a competing political vision for Afghanistan. I was friends with the various leaders of Jamiat Islami in northern Afghanistan, and unfortunately, I had already spoken out a number of times in Afghan assemblies in Peshawar against the dangers I saw coming to Afghanistan with the western funding of Islamist organizations like Hesbi Islami. Commander Asif suddenly entered the room again; he gave instructions to an assistant who soon left us alone. “We do not accept your letter from Jamiat. They have no authority in Afghanistan.” He started again, “We have searched your bag and found your camera. If you are really an aid worker why do you carry a camera?” He said this almost triumphantly, as though he had just unmasked my hidden mission. “Commander, sir,” I said, “I have to photograph the condition of the internal refugees to be able to document their situation for the organizations who have pledged money to help them.” “I don’t believe you!” he snapped. His assistant entered the room and stood nearby with his AK-47 at the ready. “You are a spy and have no permission to have entered our country. Empty your pockets!” the Commander ordered. I was carrying almost nothing on me. My captors had already searched my belongings and the only thing that was not in my pack was the travel money sewn inside my sleeping bag. Luckily, that had been left with my other Afghan traveling companions who had not been detained at the checkpoint. I handed him the only thing I had in my pocket, a small piece of paper neatly folded to protect a line of lovely Arabic calligraphy. “What is that? Let me see it!” he demanded. I handed it to him, wondering what his reaction would be when he read it. Would he be offended? It was the beginning of the first verse of the Qur’an, written for me by Qari Rahmatullah, the Qur’an reciter, or qari, for the group of Mujahideen I had been with at the border of Pakistan some days earlier. Qari Rahmatullah had the most melodious voice I had ever heard, sonorous and moving. His passionate singing was perfect for the liturgy he was reciting. He had noticed me pulling closer to listen to his recitation at the times of prayer, and he made it a point to welcome me into the group, even though he knew that I was a Christian. He spoke with me about the beauty of Islam; I could truly feel that beauty in him and hear it in his voice. One morning he had asked me if I would like to learn some Qur’anic verses. I gladly accepted. The truth is that I already knew this opening verse of the Qur’an, but I wanted Qari Rahmatullah’s friendship and guidance. He wrote the sacred verse on a piece of paper so that I could practice it. Bismillah ar-rahman ar-raheem. Al-hamdu lillahi rabi al-‘alameen. (In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful. Praise be to Allah, Lord of all the worlds.) This was the folded piece of paper I handed over to the stern-looking commander sitting in front of me. He opened it. A long moment passed. “Are you a Muslim?” he asked in a more gentle voice. “I am not, Commander, I am a Christian.” “Then how is it that you carry this sacred verse on your person?” I recounted my lifelong interest in religion and spirituality. I explained that I had studied Islam before coming to the region. I told him of my experience of listening to the beautiful recitations of Qari Rahmatullah and my desire to memorize the verse. Commander Asif’s face softened. I even thought that his eyes had become faintly moist. He motioned for the guard to leave the room and we sat quietly for a few moments. He then asked where I grew up and other details about my life, but now in a much different tone, one that was almost friendly. He spoke about how hard the war had been for him and his people. He asked about my religious views and I told him about my Catholic upbringing. He explained that all Muslims loved and revered Jesus, whom they considered to be a great prophet and ‘the spirit of God.’ He then stated that Jesus was not the ‘son of God,’ that God could not have a son. “Islam is a light for all who come to it,” he said invitingly. “I have been drawn to it and I am studying it,” I told him, “and I am in awe of the beauty I find in it.” “You have entered Afghanistan illegally,” he finally said, “but I accept that you have a mission here and I will write you a proper letter of authorization.” He got up and left the room. Shortly, a man brought in some delicious ripe melon. It was sweet, as sweet as this sudden blessing of deliverance that I felt in my heart. I was still a bit anxious that Commander Asif might change his mind, but he returned with the letter and wished me peace and success on my journey. “Thank you, and peace be upon you, Commander Asif,” I said with relief. As we were driven back to the checkpoint, I considered how frail I was. I thanked God for not putting me through a more serious test of character. I don’t know how I would have been able to handle a long imprisonment. Yet I realized I had not panicked, nor had I been without hope. The thought crossed my mind that I could still change my plans and return to Pakistan. “No, I must go on,” I decided. “This is only the beginning of the journey. I must trust in God and His plan for what lies in store for me.” Within a few hours, Abdul Hayy and I rejoined our three traveling companions who were nervously waiting at the checkpoint. The letter of authorization from Commander Asif of Chak Wardak was our ticket for safe passage through many dangerous regions of northern Afghanistan. Whenever we found ourselves in areas controlled by Hesbi Islami, this letter succeeded where our Jamiat Islami letters of authorization were useless.  Author's route during the overland trip of 1989 The whole incident at Chak Wardak would not have occurred if I hadn’t decided to separate from the three-hundred-strong group of Mujahideen at the Pakistani border. We had wanted to make the whole journey with my Afghan friend, the Jamiat commander, Haji Nurullah of Sheberghan. He had consented to protect us and our pack animals strapped with goods intended for distribution to the needy villagers of northern Afghanistan. This was not just a caravan of goods. It was a caravan of money concealed within packages of blankets and household items. The old Afghani currency still in use had been so devalued by inflation that the converted $50,000 we carried required half a dozen donkeys to haul the bundles of banknotes.  Commander Haji Nurullah of Sheberghan I had known Commander Nurullah for two or three years. He used to visit my Peshawar office whenever he came to Pakistan to apply for medicines and vegetable seeds that our foundation provided. I occasionally translated for him at the offices of other agencies, to help him get what he needed for his distant province. We had developed a good rapport and I felt that it would be safe to travel with his small army into the north. What I didn’t know is that he had other foreigners in this army—Arabs from Egypt and Yemen. The difficulties with the Arabs began almost immediately. There were a half-dozen Arabs in our party, mostly from Egypt, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. They appeared to be in their twenties and thirties. A couple of them were clearly well-educated. The most vocal and critical of them was an albino from Egypt with an imposing presence. We were at Azam Warsak on the Pakistani border when the Arabs found out that I was with the group. Commander Nurullah had tried to keep my presence a secret. He was one of several Afghan friends who had advised me to travel in disguise. Word about who I was got to the Arabs somehow and they became openly hostile toward me. My interactions with them became so disturbing that by the second day inside Afghanistan, I arranged with Nurullah to temporarily leave the safety of his group. My small band of five departed, dressed in simple clothing and without weapons, hoping not to draw attention to ourselves as we traveled north. We planned to rejoin Nurullah in northern Afghanistan to distribute the money and supplies in his caravan to internal refugees of the war. The young Arabs in his army had come to Afghanistan for war. They boasted that they came to kill infidels, meaning the Afghan Marxists who still held the cities after the Soviet withdrawal. They spoke loudly about the infidel West, loud enough to be sure that I heard them as they described me as a kafir, an impious infidel. They also said that I was a spy. I think out of embarrassment, Commander Nurullah sent his assistant to explain to me the tensions of working with the Arabs and the need for me to stay clear of them. Nurullah was in a bind. He needed money and help from the Arabs in order to make a successful journey back into the north. Their help was, however, a double-edged sword. Arab fighters were despised in many parts of Afghanistan. This was especially true in the Hazarajat where the inhabitants are Shia, the largest minority sect in the Islamic world. Most of the Shia commanders of the Hazarajat follow the religious dictates of the late Ayatollah Khomeini. He had been the architect of the Islamic Revolution in neighboring Iran. The Wahabi Arabs regarded the Shia as infidels. There had been terrible battles between the Hazara fighters and Arab jihadis traveling through their territory. By 1984, Arab influence was spreading throughout all of Afghanistan. These Islamist Arabs, at that time already viewed as fanatics in their own countries, were for the most part very angry young men who were disillusioned with their own governments. They despised the Western culture they thought was corrupting their societies. Many had recently been released from prisons in their native countries, where they had been convicted of crimes such as sedition. Afghanistan was a haven for this new culture of the “jihadi,” the holy warrior. This stereotype of the jihadi had taken shape slowly, over the last couple of decades, and was an unsettling factor throughout the Islamic world. It was based on the ideas of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and similar organizations that have existed since the first half of the twentieth century. The ideal is that of a pious young man, willing to give up an ordinary life, even his very life, for the noble cause of a pure “original Islam.” They viewed this original Islam as an ideology that could overcome both the corruption of the decadent West and the weakness of most ordinary Muslims, whom they considered hypocrites. As these Arabs came to Afghanistan, their extremist views led to friction with Afghans. In Konar province I spoke with Afghans who lamented the Arabs’ destruction of the graves of Sufi saints and of other holy places where believers came to seek spiritual intercession for their problems. The puritanical Wahabi Arabs considered this and other traditional Afghan practices to be forms of idolatry. I had also heard many stories of Afghans being chastised by Arabs who claimed that Afghans didn’t know how to pray properly. Afghans are a proud people who don’t take criticism in silence. The majority of Afghans rejected this new fanaticism, but over time it was gaining ground. Many young Afghan Muslims had begun to turn away from their culture’s moderate beliefs and practices toward this new political and military Islam that was now taking root in Afghanistan. This new form of Islam was a synthesis of the most literal and selective reading of the Qur’an, blended with an anti-Western, anti-secularist viewpoint. The competing influences that I observed in Afghanistan included the doctrines of the Ayatollah Khomeini, Arab Wahabism, and the narrow-minded Maududi Islamism that had been branching out for several decades in Pakistan. (Abu Ala Maududi had been heavily influenced by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. His movement favored a worldwide Islamic revolution that would restore the idealized caliphate of the early years of Islam.) Pakistan’s madrassas, or religious schools, had been educating tens of thousands of Afghan refugee children. In these schools, idealogues inculcated an intolerant exclusivism that condoned violence as a means of achieving their aims. The war had been raging for a decade and the gentle, hospitable brand of traditional Afghan Islam was being lost. On the eve of our departure from the safety of Commander Nurullah’s caravan, a couple of the Arabs challenged me to explain how I could remain a Christian now that I had seen real Muslim warriors. I explained, over their loud objections, that I had in fact studied Islam for many years and that what made it so attractive to me was not what they claimed about Islam at all. “Islam, as I have come to understand it, is a religion for turning to God, and historically, it has been a vessel that has preserved the science and knowledge of many cultures.” They were dismissive as I spoke about the influence of Greek, Persian, and Indian thought on early Islam, and the huge advances made in science, medicine, and philosophy as a consequence of this synthesis. “You are a kafir, an infidel!” one of them shouted, “You have no right to even speak about Islam. You are denigrating our religion with this filthy talk!” His Persian was rough and hard to understand, but I certainly got his point. “This is why we have come for jihad,” said another, “to destroy people like you and this infidel Pakistani friend of yours. Both of you blaspheme against true Islam.” The Arab man was speaking about Haji Nezakat, a Pakistani whom I had met while we were assembling at the border. The Arabs thought worse of him than of me because they had come to the conclusion that he could not be a haji, an honorific title given to those who had made the pilgrimage to Mecca. They had apparently asked him to describe certain places and rites of the hajj and were not satisfied with his answers. As hard as they were on me as a kafir, these fanatics were even less forgiving of someone they regarded as a bad Muslim. They saw Haji Nezakat as an incorrigible hypocrite. They also showed utter contempt for him because they thought that he was a spy working for Pakistani intelligence. Much later on this journey, when we rejoined Nezakat in the north of Afghanistan, I came to the conclusion that the Arabs were correct about Nezakat’s connection to Pakistani intelligence. I didn’t think so when I first met him because, after a lifetime of consuming spy books and movies, I didn’t think he had the careful, stealthy qualities needed by a real spy. Nezakat spoke flippantly about everything and claimed, quite openly, to be working with the intelligence services. At first, I frankly thought he might be a bit crazy. It wasn’t until later that I realized that his behavior and the many other wild things he said were actually a carefully calculated smoke screen. I eventually learned that Nezakat was working for the Pakistani government to monitor the distribution of American-financed weapons. In time I came to admire the boldness of his ruse. I also enjoyed his company immensely, as I traveled in this war zone overpopulated with fanatics and manipulators. Nezakat could walk in and out of almost any situation with his irresistible sense of humor and a naturally funny appearance. His face somehow captured a stern expression floating on a sea of mirth, enough to crack me up without him saying a thing. When he opened his mouth, it was always to spout some crazy nonsense or a lurid joke. I was surprised that he could get away with the irreverence and dangerous iconoclasm that he engaged in. Together we visited Maulawi Shahabudin’s home at Sangcharak in the north of the country. The Maulawi, a very dignified older man whose title indicates religious authority, was the highest ranking Hesbi Islami commander in the whole region, and not a man to be trifled with. As we were being served the meal by the Maulawi’s adolescent son, Haji Nezakat suddenly pretended an amorous interest in the handsome boy. He rolled his eyes lasciviously and asked the Maulawi, "Who is this comely young lad?" The shocked Maulawi gave him a stern, offended look, and for a brief moment everyone at the meal feared that disaster was imminent. But just as quickly, the Maulawi broke into a laugh that filled the room. The rest of us joined in the laughter, and the moment was saved. Practically every day that I traveled with Haji Nezakat I saw him use this kind of comic irreverence to break through the hardness and sadness that we encountered. I wanted to photograph him but he warned me that spies shouldn’t be photographed. Though later, when we met up again in Peshawar, he gave me two photos of us together, photos taken with his own camera. He had smiled and given me a conspiratorial look, then handed me the photos, all the while looking carefully from side to side, feigning secrecy.  Author with Haji Nezakat in Afghanistan It was obvious, I thought, why the fanatical Arabs couldn’t appreciate him. They did not possess a sense of humor. In fact, I never saw them laugh. They only smiled when talking about their experiences in battle. Our tedious and sometimes dangerous journey on foot and horseback into the north of Afghanistan also had its joys and satisfactions. Fortunately, I had learned to ride horses in California from a friend; Lynda took me on rides along a beach near San Gregorio and taught me how to feel at ease on these independent and capricious animals. We traveled around the Marxist-held cities through wastelands and forests, over rivers and through high mountain passes. I enjoyed the long days of travel through these remote areas. There was plenty of time to think about things that really mattered as our small band slowly moved northward. We rose each day at the break of dawn after a few hours of often uncomfortable sleep on rocky ground or in lice-ridden tea-houses. After a small breakfast of bread and tea, we’d begin the day’s twelve-hour trek along impossibly narrow, dangerous trails, often winding along the edges of precipices where my companions would remind each other of the demise of various horsemen and even caravans that had vanished into the void below. Despite the accumulating weariness of these days of travel, we remained in good humor. During the long days, I thought about the Islamist influences I saw taking root in Afghanistan and I wondered what impact they would have on the gentler, more tolerant Afghan beliefs. Free from the tensions with the Arabs, I was in a joyful mood. I thought about my own life. The reason I had come to Afghanistan in the first place was my love for Afghan culture. I could never forget the sincerity and kindness that I first felt with my Afghan friends in the United States. I was aware of the rich heritage of Afghan culture that reached back into earlier centuries. For a number of years I had been studying the Persian classics, some of them written by Afghans like the now-famous Jalaluddin Rumi. Later in my journey, I was astonished to find people in the rural valleys of northwestern Afghanistan that still speak a Persian almost identical to the language of Rumi’s masterpieces. Long before traveling to Afghanistan, I had been deeply moved by the English translations of these poems. And so I had come to Afghanistan searching for traces of this high-minded culture that had kindled the flame of my hopes and dreams. As I rode up the trail on my lethargic horse, I thought about how this brilliant culture of Islamic spirituality was quickly disappearing in the face of the suffering caused by the war. Traditional Afghan culture was being eroded by the fanaticism of the Wahabis and Maududis. It struck me that this small-minded extremism was incompatible with the Islam that was, at one time, vast enough to hold and cherish the knowledge of the world it had conquered. That world stretched from the Atlantic Ocean into the reaches of China. I rode along replaying the memory of my chance meeting three years earlier, in 1986, with the extraordinary Afghan poet laureate and mystic, Ustad Khalilullah Khalili. My brief friendship with him near the end of his life had been deeply influential, largely because he openly manifested the wisdom, broad-mindedness, and religious tolerance described in the classical literature of Sufism. He too had voiced the fear that these values were disappearing from Afghanistan. Riding up the steep, narrow trail, I remembered our warm conversations. Once, out of concern that as a Christian I wouldn’t be able to understand Islamic mysticism, I asked him, “Does a person need to be a Muslim to grasp the spirituality of Sufism?” “The heart of the lover of God should become purified and polished,” he answered. “Then he would see the meaning of the Qur’an written on the unfolding rose petals of his own heart. Whoever has such a heart as this is a Sufi and a real Muslim.” I recalled that the Sufis often carry the sobriquet of jasus al-qalb, “the spy of the heart.” I thought of how Ustad Khalili had immediately grasped my essential self. He had sensed my yearning and my disillusionment. He knew that I had come to Afghanistan in search of the meaning of life. Afghans that I encountered during those years no doubt wondered about the agenda of a young foreigner traveling on horseback through their war-torn country, dressed in native clothing and speaking the local language. I could sometimes feel them trying to peer into my intentions as we spoke about the war. They often expressed their admiration at my willingness to go into the war zone. They asked about the injustices and suffering that I had seen. I would share with them my darkest experiences and also recount the many acts of kindness and bravery that I had witnessed. The Afghans I met were often saddened and weary. They saw themselves pinned between the relentlessly destructive civil war and the destabilizing interference of several outside powers, not least the United States. It was understandable that they harbored at least some suspicions about the motives of a foreigner, and conceivable that many in the war zone thought I was a spy. They could not fathom my real purpose for being in Afghanistan. Ustad Khalili, however, had correctly spied into my heart. He had understood my search for meaning. In the years since his death, I often felt his presence and have occasionally dreamed of him. As my horse reluctantly climbed the trail along the bank of a lovely stream, a hoopoe bird, the symbol of spiritual guidance, suddenly flew past and landed in the grass ahead. It looked our way, and expanded the crest feathers of its head into a crown. I remembered the hoopoe from my dream the night before, flying brightly past me. He is with you wherever you are >>

|

| Site Designed by James Dilworth | © Robert Abdul Hayy Darr, 2006 |