1 : Of Spies & Rogues

2 : He is with you... 3 : The Great Buddhas 4 : Recollections 5 : A Broken Peace 6 : The Salt of the Earth 7 : With Friends Like This 8 : An Ill Wind 9 : What the Devil... 10 : Not by Bread Alone 11 : A Loss of Face 12 : The Water of Life 13 : Shades of Mercy 14 : Afterword Appendix

Buy the book from Amazon Buy the book from Amazon45 color photographs, several sketches, and 3 maps. The Spy of the Heart can also be ordered direct from the author : Send a check for $20 to Real Impressions, P.O. Box 714, Sausalito, CA 94966, USA. incl. Postage & Packaging.

|

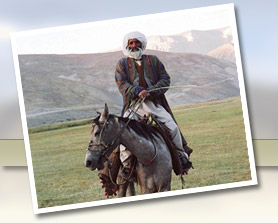

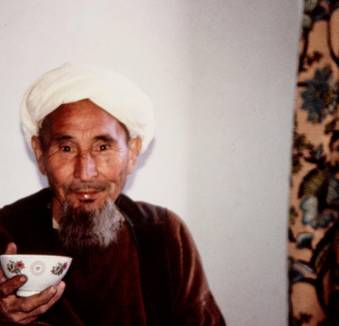

4. RecollectionsMehmet Serif was not how the gentle, soft-eyed man in front of me used to spell or pronounce his name. He was born and raised in northern Afghanistan with the name Mohammad Sharif. He had, like hundreds of other Turkoman refugees from Afghanistan, accepted the changes to his name. This was just one of many changes the refugees learned to accept while adjusting to the community in central Turkey they now called home. It was my good luck to have met Mohammad Sharif and the powerful Tukoman leader Abdul Karim Makhdum there. Were it not for this connection to Abdul Karim, I might have been killed or imprisoned by his followers, the Turkoman fighters in northern Afghanistan who instead offered hospitality and help. That is how things work in this part of the world. I already had friends from the Afghan diaspora living in the United States. The trip to Turkey in 1985 was my first visit to Afghan refugees resettled in the Islamic world. By then, Afghans made up the largest single refugee population in the world, some five or six million of them, most in Pakistan and Iran. Far smaller numbers of refugees had been resettled in Turkey. At the time of my trip there, I had not even thought of going to Afghanistan, especially not with the ongoing carnage of the Soviet occupation. While planning this vacation to Turkey, I heard about a small population of refugees from northern Afghanistan. This aroused my curiosity because I had already contributed to a charity supporting Afghan refugees. I admired their rich history and culture and empathized with them. I was better informed than most people about Central Asia because of the years I’d been a student of Sufi literature, in particular of Jalaluddin Rumi. Rumi, an Afghan originally from the region around Balkh in northern Afghanistan, was now one of the most widely read poets in the world. English and French translations of his mystical poetry had inspired me to study classical Persian, in order to better appreciate him.  Mohammad Sharif on left I had only a rudimentary grasp of Persian when I first met Mohammad Sharif in Tokat. Luckily his beginner’s English was more conversational than my Persian, and we were able to communicate. None of the other Turkoman refugees there spoke a European language. Those few days spent with Mohammad were the basis for a rewarding friendship that spawned a small income-generating project to help the refugees of his community. We met with Turkoman refugees in Tokat and some of the nearby villages.The Turkish government had provided the refugees with simple block-apartment housing located in various small cities and towns of central Turkey. The Turkoman had furnished these drab spaces with their colorful carpets and wall hangings. We sat on long, comfortable cushions lining the walls. There were endless hours of drinking sugary green tea and eating small cakes and other sweets while we told each other about our lives. The people we met were gracious and warm. The brightly-dressed women interacted quietly in the background, listening as the men engaged us in conversation. They brought tea and food and stoked the coal stove that kept the cold March wind at bay. Their children were noticeably quiet and well-behaved. The less timid ones sneaked their way closer to me to get a better look at this pale, blue-eyed foreigner. My Turkoman host could see that I was delighted by the antics of their adorable children.  Turkoman refugees “Go sit with kaakaa, your uncle,” the men encouraged their children. The bold ones came over and presented their heads for me to kiss. They smiled or laughed, delighted with themselves, as they approached me shyly. I thought how wonderful it was that they had all been raised to think themselves dear enough that even a stranger would want to kiss their heads.  A Turkoman refugee elder of Tokat I departed after these few magical days of getting to know the refugees, carrying three small handmade rugs they asked me to sell for them in the United States. My first meetings with them left me with a positive impression. These uneducated Turkoman refugees had a certain presence, a luminosity of heart that shone in their eyes. They possessed a strength of character that transcended their experiences of misery and suffering that resulted from the war in their homeland. Upon returning to the United States, I sold their rugs and sent them the money, thinking it was just a small favor. Within a month, there was a shipping notice in my post office box. To my surprise, there was a package with a dozen rugs for me to sell. What was I getting into? I was a professional woodworker, not a rug salesman. But I did want to help them. I had warm memories of their dignity and hospitality, and their need. I was completely inexperienced in such matters, so I rang up my savvy and well-to-do friend, Sam Barakat, for advice. Sam was the American-born son of a Palestinian father and an American mother. I had known Sam since my early twenties, and we shared an interest in the cultures of the Middle East. Sam told me that if I really wanted to help the Turkoman refugees in a professional manner, it would be best for us to start a small non-profit organization. We established the Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation and over the next five years, Sam was a huge help, both morally and financially, in forming and running the foundation’s projects. His support gave me the confidence to expand on our small beginnings. Before I knew it, we were running an income-generating project that enabled the Turkoman refugees to produce dozens of rugs as well as leather jackets from their home workshops in central Turkey. These became the model for the income-generating projects that we later started in the refugee camps in Pakistan. During the mid-1980s, I traveled to Turkey two or three times a year to monitor our projects. From the outset, I dealt with the complexities of establishing and maintaining standards of quality—perhaps the biggest problem with all of our projects. We had guaranteed to buy the goods in advance of manufacture in order to provide the refugees with needed income. The refugees were, however, accustomed to a completely different system in Afghanistan, where they had to produce something of high quality in order to sell it to dealers in the competitive Afghan market. Our projects were at a commercial disadvantage because the wages were guaranteed no matter the quality of the work and the product generally suffered from a relatively poorer quality of materials as well. This often made the refugee products less marketable. During those years I traveled with Mohammad Sharif to the home-workshops of individual refugees to check their work and encourage them to improve the quality. On my second visit during 1986, Mohammad told me that Abdul Karim Makhdum, a famous leader of the Turkoman people, wanted to meet me. I was delighted at the prospect because I had read about this tribal chief. He had apparently, in the early years of the war, done everything possible to negotiate with the Communist leaders of Afghanistan, to try to reduce the bloodshed; he went into exile in the early 1980s. When I met him, he was comfortably settled in central Turkey, but he lamented the loss of his native land.  Exiled Turkoman leader, Abdul Karim Makhdum “Abdul Karim Makhdum want thank you,” Mohammad translated in a thick accent during our first meeting. “He want thank you much for your helping Turkoman people. You not knowing how much suffering our people had. They suffer very much in Afghanistan with Communists. They are good Muslim, good Muslim. They not behave like Communists.” Abdul Karim, a very noble looking middle-aged man sporting a well-tended goatee and wearing a fine suit and tie, glanced at me emotionally as Mohammad translated his words. “We come Turkey. Turkey ask us. Turkey our brothers. Have almost same language. They help us very much. They help us, but Turkey not Afghanistan. Not same. We thanking them but here not same.” As I listened to this noble leader’s words translated into broken English, I pondered the irony of history. The Turkoman were once a powerful tribal group that only a century earlier had been feared for the ruthless raids they carried out on villages in the north of Afghanistan. They were now reduced to handouts from the Turkish government. The tribes had been pacified and assimilated into Afghanistan by the first half of the twentieth century, but their past deeds had not been fully forgotten. Abdul Karim showed me some truly beautiful rugs that he had commissioned to have some of the resettled Turkoman women weave. The Turkoman are famous for their intricate weavings, among the finest in the world. The small rugs he showed me were tightly woven with perfectly executed repeating geometric designs that were symbols of the various Turkoman subtribes. When Abdul Karim asked for my opinion about the marketability of the rugs, I told him about the difficulties we had encountered while introducing Afghan rugs into the United States on a large scale. American buyers are rarely drawn to the bright red color of these traditional pieces. By 1987, though competition was stiff, we had successfully marketed some of the same rug designs in softer colors. The weavers in Pakistan and India had already pioneered the use of softer colors and they dominated the world market. I explained all of this to Abdul Karim, who was somewhat surprised at my description of the American market. He found it odd that people would try to “match” a rug, a piece of art in itself, to the furniture or color of a room. Most sophisticated Easterners valued a rug for the mastery of its design and workmanship, as well as its authenticity. But it was necessary to employ large numbers of refugees and market factors won out. Abdul Karim accepted my opinion that some changes to carpet colors and designs would have to be made, at least temporarily, in order to feed his people. In late 1987, Mohammad Sharif and I took a trip from Tokat to Konya, a city famous for housing Rumi’s tomb. I wanted to see if the rug stores there would be willing to sell some of the rugs made by the Turkoman refugees. The Turkish rug market has always been quite competitive and innovative. I hoped I would be able to introduce something out of the ordinary to a couple of rug dealers I knew in Konya. Along the way, I asked Mohammad if he had ever been to the tomb of the Sufi poet, Rumi. “No, Sikandar, I not gone there yet,” Mohammad said. “I wanted make the pilgrimage for much time. Maulana Balkhi is name we use for Rumi. He was born in Balkh, an Afghan town. It is near my old home, Mazar-i Sharif. When he moved to this part of world, he also take name Rumi. Are you wanting see tomb?” “Yes, I want to see the tomb again,” I answered. “I visited it last year, Mohammad, and it was quite an extraordinary experience. His tomb really has an unusual presence of sacredness and peace. I have never felt anything quite like it.” By that time I could speak with Mohammad mostly in Persian. With every visit to Turkey, our conversational abilities improved—we were each making great strides in our language studies. “He was very great man,” Mohammad said. “He was Sufi saint and his book Mathnawi is deep, very deep.” While driving along, Mohammad occasionally checked his watch. He asked me to stop at a convenient mosque when it was time to say his prayers. The Turkoman, like most people in Afghanistan, were Hanafi Sunnis, of the same Islamic school as the majority of Turkish Muslims. Mohammad could enter any mosque and perform the same devotional rituals he had learned as a child in his native land. We arrived in Konya around midday. Like the suburbs of most Turkish cities, Konya is built up in huge, unattractive block apartment buildings. We drove into the more charming old city and found a hotel near Rumi’s tomb.  Rumi's tomb in Konya The tomb’s turquoise dome can be seen from far away. Its unusual shape is something like an upright cylinder divided by vertical ridges, topped by a cone-shaped roof, all covered in turquoise tiles. We entered the peaceful, dark interior of the tomb and stood for a moment as our eyes adjusted to the dim light. We could soon make out various panels of beautiful calligraphy on the walls. Suddenly, I saw a poem that was familiar to me, one that was incorrectly attributed to Rumi, but which nevertheless captures the great poet’s open-handed mysticism. Baaz Aah, baaz aah, har anchih hasti, baaz aah. . . it began. Come, come! whatever it is that you are, come! Whether infidel, Magian, or idol worshipper, come! Our court is not a place of despair, so even if your vows are broken a hundred times, come! The poem certainly reflected Rumi’s temperament and teaching. He had been criticized in his own day for letting all and sundry attend his public devotional gatherings, where he used music—sometimes even the popular music of his time. Some of the religious authorities denounced the ecstatic character of these assemblies. Rumi became known as the teacher of love. He spoke of God’s love for His creation and the salvation made possible through the love of God in this world. Rumi had become an ecstatic mystic in his middle age, after a more conventional career as an imam. He had, suddenly, lost the sobriety of overt piety to the force of love overflowing in his heart. He started exhibiting unusual behavior, like dancing to the rhythm of the hammering of goldsmiths in the bazaar. According to the biographical records, these changes came about when Rumi’s own identity merged with that of his teacher, Shams of Tabriz. In the intensity of his spiritual love for this enigmatic mystic, he even wrote poetry in Shams’ name. Rumi’s is perhaps the most famous story of how a renowned teacher suddenly became a student—and from new inspiration overturned the worldly conventions of the time. After his illumination, Rumi had a fundamental shift of perspective. It was said that he treated everyone the same: prostitutes and the insane as well as the most dignified citizens of the cultural capital of his time. The twelfth century of Rumi’s day were very hard times. The Mongols invaded all of Central Asia and relentlessly and systematically destroyed the accomplishments of more than five hundred years of Islamic civilization. Rumi himself was a refugee of that catastrophe. His father took him out of northern Afghanistan in the early part of the thirteenth century, just before the Mongols destroyed the region. Far away Konya, situated in central Turkey, was at the edge of this turmoil throughout most of Rumi’s life. By the end of the thirteenth century, Konya succumbed to Mongol rule as well, but it was not destroyed like so much of the Islamic world. By the fourteenth century, the Mongols had converted to Islam and became the stewards of an Islamic renaissance.  Rumi's tomb, Konya Mohammad Sharif and I made our way into the dimly lit building toward a raised sanctuary enclosing Rumi’s tomb, regally draped in embroidered calligraphy. The tombs of his spiritual heirs are crowded nearby, his son’s tomb lies next to his own. I walked up to the silver gate of the enclosure and, as is the traditional dervish practice, raised my hands in supplication. People often come here to ask for the saint’s intercession in personal matters. Dervishes usually don’t ask for material goods. Instead, they say a prayer for the saint’s departed soul and pray for their own greater spiritual intimacy with God. I stood for a while in silence, I could feel the tomb’s special presence just as I had the year before. Or was this feeling just in my imagination? Perhaps it was the energy of countless prayers of unnamed dervishes that had accumulated within these walls. Or was what I felt really coming from the tomb of the saint? I had no doubt that the feeling was real. It was an unmistakable sensation of spiritual depth and peace. This was not a customary emotion or an ordinary sensation. It was an expanded awareness, a subtle witnessing of an immaterial or spiritual presence at the tomb. Dervishes cultivate their sensitivity for these kinds of spiritual perceptions by first freeing themselves from habitual mental and emotional experiences. This is done through meditative and devotional practices that usually involve concentrating one’s attention toward the Absolute while letting go of the various other events that occur in the mind. There are diverse practices to achieve this “emptying the house of self-preoccupation” but all of them depend on cultivating one’s attention to gently withdraw from usual preoccupations. The specific forms of sensations, thoughts, and emotions are observed and then released from one’s attention, which then becomes available to sense the Source of things. The Source of things is witnessed as the fundamental ground of the existence of things, it is always present, whether observed or not. After Ustad Khalili’s death, I undertook a more regular practice of the particular cultivation of presence with God that he had advised. In the Sufi way, this practice is called zikr, best translated as “remembrance” or “invocation.” The origins of the practice of zikr can be found in the revelations of the Qur’an. “Remember Me and I will remember you,” Allah says. “The invocation of Me brings peace to the hearts.” “Remember Me standing, sitting, and lying on your sides.” These verses clearly advocate devotional practice. As I began to immerse myself more into the metaphysics of Sufism, I encountered surprising parallels between the Sufi practice of “remembrance” and the ancient Greek and Neoplatonic ideas about remembrance as a form of “unforgetting.” According to this view, the practice does not lead one to acquire a new capacity or characteristic, rather it leads one to strip away those attitudes based upon desire and fear that hide what each of us once knew—the fundamental relationship we have with True Reality. On the walls of Rumi’s sanctuary I read a clear reference to this truth, from the introduction to his masterpiece, the Mathnawi: Har kasi ku dur maand az asl-i khwish, baaz juyad ruzgaar-i wasl-i khwish. Whoever has remained far from his origin Again seeks after the days of that union. For Rumi, this is a spiritual reunion that takes place in the heart, meaning the inner consciousness of a person. In Islamic thought as well as in other spiritual traditions, the heart or mind is often compared to a mirror. Rumi explains in the Mathnawi, Do you know why your mirror does not reveal? It is that the tarnish has not been scoured from it. Elsewhere in the Mathnawi he writes, Each, through the capacity of an illumined heart witnesses spirit’s Mystery to the extent of its polishing. The Qur’an states that, “What they have acquired has rusted over their hearts.” Muslim mystics and the ancient Greeks held that the heart was the seat of consciousness. According to the Qur’anic verse, the self is drawn toward whatever appeals to it, often to sources of physical and psychological pleasure. The acquiring described in the verse refers to the clouding effect of our accumulated experience in the sensory world. Instead of experiencing the things of the world as reminders of God’s grace and power, the average person becomes possessive or fearful of losing these things. Ustad Khalili had advised me to engage in a daily practice of zikr to enliven my sensitivity to the presence of God. I noticed that this sensitivity increased when I was in certain places, like Rumi’s tomb. After Khalili’s death, I continued my search. I met other local Sufis who accepted me as a seeker and occasionally taught me their own spiritual practices. I was particularly drawn to what I had read about the Naqshbandi fraternity. The Naqshbandis are one of the most widespread orders of Sufism. I initially encountered followers of a branch of this order in Pakistan in 1987. These Naqshbandis of the Mujadiddi line were quite active in Pakistani spiritual and religious life. I met some members of this group at Peshawar University who were studying the life of Shah Waliullah of Delhi (d. 1762), historically one of the order’s greatest teachers. A number of these students came from the outlying villages where the Naqshbandi order had been active for centuries. Members stressed the devotional rituals of Islam and were highly observant of the many sayings and habits of the Prophet Muhammad. They were gracious people who welcomed me as a guest into their fold. They soon advised me to convert to Islam and follow the Prophet’s example and behavior as described in the historical records of his life, the sunnah. They followed his example in a most literal sense, even using the miswak, a special twig, to clean their teeth just as the Prophet had done. I asked one of their elders if the Prophet might not have used dental floss and a toothbrush if he were living today. I certainly admired the Prophet’s inclination to hygiene, I told him. “There is blessing in following the example of the Prophet, upon him be peace, even in small things. That is why we use it,” he explained I enjoyed the warmth and shared values of their company. But I also felt uncomfortable with the incessant expressions of piety that filled our conversations. It seemed to me that hypocrisy always lurked in the shadows of this kind of religious posturing. I had come to believe—after observing myself and others—that the cultivation of a religious persona can lead one to disown other aspects of personal experience, and make one false and neurotic in the process of this denial. In several conversations with my new acquaintances, it became clear that some of them were actually frightened of their own thoughts and feelings. This attitude, not surprisingly, engendered an abundance of unwanted thoughts and feelings, which they described as “satanic suggestions” or “promptings of the lower self.” They spoke of their struggle to distance themselves from their basic human nature. This path of self-rejection seemed, at the very least, inefficient. Or maybe, once again, my childhood in Tahiti made me pull away from expressions of spirituality that hold human nature in contempt. Their attitude did make me think more about my own culture in the United States, which on the West Coast where I lived was quite materialistic and hedonistic. Spirituality didn’t play a strong part in the lives of many of the people that I knew there. Many of my acquaintances were affected instead by existential apathy and confusion about the meaning of life. I was grateful to have always felt some measure of my own spirituality despite the various problems in my life. Yet in spite of my faith in God, I had not committed to a life that was centered on religion and spirituality. I later met other members of the Naqshbandi order in Turkey, where the fraternity had been very powerful for several centuries. Some of these teachers were quite erudite, open-minded, and helpful to my own spiritual search. One such elder was Ahmet Yivlik whose baraka, the spiritual power of the friends of God, was tangible. I could feel a subtle ecstasy in his presence as he spoke about the dervish path. He was a knowledgeable commentator on the complex teachings of Ibn al-‘Arabi, which he made easier for me to understand. I especially benefited from the time I spent with a group of Naqshbandis in northern Afghanistan, who claimed that their organization had been in the region for centuries, since the death of the eponymous founder, Bahauddin Naqshband (1317–1389). Jamaluddin Rahmatullah, a man who was to have a profound impact upon me, and others from this circle preserved the clarity of the doctrines and practices of the Naqshbandi teachings that were true to the order’s oldest and most fundamental writings. What I found particularly appealing about these Naqshbandis was their cultivation of an expanded awareness of spiritual truth within ordinary life. They were natural and down-to-earth, they did not wear special clothes or publicly advocate unusual beliefs. Their group included many farmers and tradesmen and some of the few artists and calligraphers who remained in the war-torn region. Sadly, many of them were obliged to join the military struggle required to preserve their communities from the Marxist attacks that had plagued them since the war began in 1979. When I first met members of the Naqshbandi order scattered through parts of Jowzjan and Faryab provinces I was still a Christian. But unlike many others I had met, they did not harp on my need to convert to Islam. All of them, of course, were devout Muslims. When the subject of Islam came up, they would only say that God draws people to Islam if He wills and that there was no compulsion nor forcing of people toward religion. Perhaps this gentleness in their approach drew me to Islam.  Commander Hafizullah Arbab of Faryab At the time of my travels to these provinces—Jowzjan and Faryab—in the late 1980s and in 1990, I was able to travel freely within the territories under the jurisdiction of Hesbi Islami and Jamiat Islami because I had managed to establish trust with both parties. I visited a number of dervishes from the Naqshbandi fraternity that lived in and around the area controlled by Commander Hafizullah Arbab, a formidable Jamiat leader of the Uzbek people whose headquarters were at Almar in western Faryab province. At the same time, I worked on road projects and emergency food distribution with the Hesbi Islami commander, Engineer Nasim. His center was at Darzab in Jowzjan province.  Author with Commander "Engineer" Nasim These commanders offered me their trust and cooperation, I think in part because of my interest in the Sufi way. We had many conversations about religion and mysticism which led them to understand my reasons for coming to Afghanistan, how it was more than just to help with humanitarian work. One day in mid-1990, I was in Almar at the headquarters of Hafizullah Arbab when Sufi Abdullah, an acquaintance of his from the region of Badghis arrived. He had several disciples with him and they asked to meet me. “We wish the peace of Allah upon you, brother Sikandar,” Sufi Abdullah said. “And peace upon you,” I answered. “I wanted to meet you and to see with my own eyes the Christian who has come to help our people. Your name has become well-known enough that I have heard of you in my own province, some miles from here.” “You are very kind,” I said. “It is my honor to be able to try to help the people of this region. I am not used to seeing as much suffering as I have seen in the villages of this area. Naturally, I feel obligated to do what I can.” Sufi Abdullah continued to converse with me in polite pleasantries and questions about my life back home. After half an hour or so, one of his students asked permission to speak. Sufi Abdullah nodded his approval. “Peace upon you, Sikandar, it is my great pleasure to meet you,” he said. “I have never seen a foreigner such as yourself and I am joyful to spend time with you.” “Thank you for your kind attention,” I replied. “My joy in meeting you is great and would be more complete if I could ask you about your religion. May I ask you a question?” he inquired. “Yes, of course, why not?” “I have heard that you have studied Islam extensively and that you have even performed the fast of Ramadan. Yet I have also heard that you have not come into Islam. Is this true?” “Yes, this is true,” I told him. “I have studied many religions and I am attracted to Islam but I remain a Christian. It is the religion of my upbringing.” “I hope you will permit me to say what is in my heart, which I say out of respect and care for you,” he continued. “You have done so much for our people that I feel a bond with you. I must ask, may you permit me, that if you know of the unsurpassable virtues of Islam, how is it that you do not convert to this faith, which is the completion and seal of the revealed religions? If you know that your Christian faith has been superseded by this revelation, how is it that you not change your faith to Islam? Surely there is an eternity of difference to you, Sir Sikandar.” Sufi Abdullah was silent but did not seem entirely pleased with the timing of the disciple’s speech. His words, though kind and eloquent, were nothing new to me. Although the Afghans are of diverse ethnicities, religiously, they are almost a monoculture, with nearly one hundred percent of the population being Muslim. Even if I had not been on a spiritual quest, I would have found myself forced to examine my beliefs, explain them, share them, and consider the beliefs of others—this is part of living in a world where people are believers. These conversations were more difficult in rural Afghanistan because almost no one had ever even met someone from another faith. Their understanding of Christianity was virtually nonexistent. “Well you see, dear brother,” I said, “I too was raised with a particular religion which I came to believe was uniquely the truth. At this time, however, I no longer think in this way about religion. Are religions really so different from each other? Do they not each call us to God? I am trying to hear that call and answer it as best as I can. In any case, may I quote a poem in answer to your question?” I inquired. (Poetry is commonly used in exchanges of dialogue in this part of the world.) “Oh, that would gladden me,” he replied. “It is a poem that I learned long ago by the Sufi Omar Khayyam. He writes that, In idol temple and madrassa, in cloister and synagogue Some fear hell’s torment while others yearn for heaven. Yet whoever is aware of the spiritual secrets of God has not planted such seeds as this within his heart.” The young man looked at Sufi Abdullah and asked him if this was really a poem by Omar Khayyam. “Yes, it is, and beautifully recited by this Christian,” said Sufi Abdullah. “Perhaps you should study with him for a while instead of me,” he added.

|

| Site Designed by James Dilworth | © Robert Abdul Hayy Darr, 2006 |