1 : Of Spies & Rogues

2 : He is with you... 3 : The Great Buddhas 4 : Recollections 5 : A Broken Peace 6 : The Salt of the Earth 7 : With Friends Like This 8 : An Ill Wind 9 : What the Devil... 10 : Not by Bread Alone 11 : A Loss of Face 12 : The Water of Life 13 : Shades of Mercy 14 : Afterword Appendix

Buy the book from Amazon Buy the book from Amazon45 color photographs, several sketches, and 3 maps. The Spy of the Heart can also be ordered direct from the author : Send a check for $20 to Real Impressions, P.O. Box 714, Sausalito, CA 94966, USA. incl. Postage & Packaging.

|

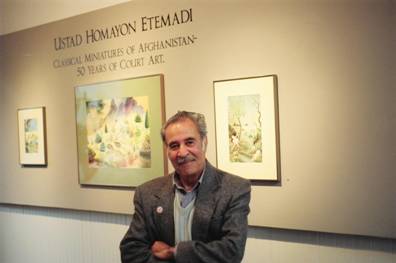

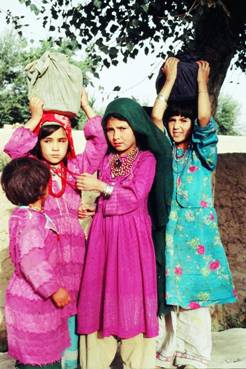

3. The Great BuddhasThe trail became steeper as we approached Haji Gak, the high mountain pass that opens into the Hazarajat. The Hazaras are a Mongol people who have inhabited this region for centuries. Hazara means “the thousand,” and refers to the thousand settlers that Genghis Khan’s army supposedly brought here after they slaughtered all of the inhabitants in revenge for the death of Genghis’s grandson, who was killed at the capital Bamian. The Mongols would have marveled at the great Buddha statues that stood carved in the cliffs facing a broad cultivated valley. The descendents of those Mongol settlers eventually became Shia Muslims, a minority in Afghanistan. Hazaras are looked down upon by most of the other Afghan tribes, out of religious intolerance and also because of the Hazaras’ extreme poverty, largely a result of their isolation in one of the coldest regions of Afghanistan. Because of their resistance to Afghan domination in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when they were finally conquered, they were subjected to abuse and made slaves. Most of the laborers in pre-war Kabul were servants of Hazara origin. Among other ethnic Afghan groups, there remains a denigration and mistrust of Hazaras. There is even an expression, chesm-i Hazara, meaning “the [envious] eye of the Hazara.” In early September the air was already quite cold at night. We stopped each dusk at a samowar along the way for safe shelter until early the next day. These small inns provide meager food and a place on the floor or the roof for the traveler to make his bed. Our dinner usually consisted of a simple shurwa, or soup, made of onions boiled in salted water to which was added whatever else was at hand, occasionally even a piece of meat. We’d break off pieces of Afghan flat bread and drop them into the large bowl placed between us. Once they absorbed the shurwa we’d scoop up the meal with our fingers. We met all kinds of people at these inns, mostly small groups of Mujahideen. To avoid danger, I passed as a northeastern Afghan from the Panshir region. The latter often had, like me, paler skin and blue eyes. The other guests were simple, uneducated people who accepted my appearance without a second thought. Conversations with them were simple and down-to-earth. From here on into the north of Afghanistan, I did not see or hear of another European or American foreigner. I was immediately struck by the sheer beauty of the region. Climbing up to the pass, we paused at vistas of the beautiful valleys below. Streams of the clearest water cut through canyons of stone. In places there were hot springs mixed into the streams. I yearned to slip into one of the pools, but there was no time, we had to keep moving. We were in the habit of rising before dawn to drink a quick cup of tea with bread and dried fruit before getting on the road. It was the same routine each long day. We walked until dusk brought us to slumber’s release in the nearest samowar. Our small group consisted of four Afghans and me. Three of my Afghan companions were ethnically Uzbek—Mohammed Ali, Asadullah, and Abdul Hayy Begzadah. Mohammed Ali was the office manager I had hired three years earlier to run our foundation’s programs in Pakistan. Asadullah and Abdul Hayy were relatives of his; they had made this journey north on several occasions. They were responsible for arranging our lodging and preparing our food. The last person in our group was a kind old man named Burhanuddin. He had approached us at Angurada on the Afghan border just before we separated from Commander Nurullah’s group and asked to join us for the safety in numbers; he offered his services as a guide in exchange. Burhanuddin was Tajik. Though the others voiced their reluctance to have him along with us, I insisted that he be allowed to join us. I found Burhanuddin dignified and well-informed, and I immediately enjoyed his accounts of the customs of rural people. He seemed familiar with all of the tribes in the region and was himself from the north of the Hazarajat. With the many dangers inherent in this kind of travel, the decision to allow him to accompany us turned out to be very wise.  Burhanuddin Young Abdul Hayy and I chatted as we walked ahead of the others. As I got to know him better, I grew ever fonder of his sincere manner. I was still very grateful for the way he intervened on my behalf when we were detained at Wardak. We had since relived our experiences several times, talking about how things went for us individually after we were detained and separated. He also seemed to like me quite a bit ever since that incident. Abdul Hayy was in his late teens when he first came to Peshawar from a remote rural village in the north of Afghanistan. He was from a noble family in Faryab province, far from the more cosmopolitan life in the Afghan capital, Kabul. It was only natural that he thought that the only viable religion in the world was Islam. He didn’t know any non-Muslims except me and had never studied the beliefs of other religions. Out of fondness, he would occasionally nudge me about Islam. “Sikandar,” he said, addressing me by the name I carried during those years, “We were very lucky. The Hesbi Islami people can be ruthless. We were protected by God and by the truth of Islam. Are you not drawn to Islam?” His genuine smile greeted me as he spoke, revealing the irrepressible joy and innocence that I came to rely upon from him. Now in his early twenties, his manner, speech, and the pride he took in his dress and appearance could have found him in a Prince Valiant tale. I felt his sincerity and mythic stature all the more after his bravery at Wardak.  Abdul Hayy Begzadah “I’ll tell you Abdul Hayy, I wasn’t sure how Commander Asif would react when I emptied my pocket and gave him the Qur’anic verse. I am relieved that things turned out as well as they did. You know that I’ve thought about Islam but I’m just not ready yet to make such an important decision.” I described to him how my father would ask me, when I returned from each trip to this region, if I was still a Christian. This is how I explained the matter to Abdul Hayy and the others. It is true that my father would inquire about what I was really getting into in Afghanistan. He was well aware of my lifelong interest in other religions and he knew that I was studying Sufism. He had occasionally voiced his worry about what he perceived as a growing Islamic political threat in the world. While his questions were always indirect, they revealed his anxiety about my attraction to Islam. Abdul Hayy asked me a question that I was frequently asked by my Afghan companions: “If you are really so interested in Islam, why have you not become a Muslim?” My companions were aware that, earlier that year, I had kept the month-long fast of Ramadan, as an experiment to better understand the religion. I think they felt let down that I had not converted to Islam by the end of the month of fasting. Afghans refer to their fathers as qibla gaah, or “place of worship,” such is their deep respect for them. I had found that I could more easily explain my ambivalence about converting to Islam by saying that I wasn’t sure how my father would react. This excuse was, at least metaphorically, true. If I did become a Muslim, I wasn’t sure what impact the decision would have on my life within my parent culture, and I was in the process of thinking all of this through. “It’s your father, isn’t it?” Abdul Hayy asked. “Yes, Abdul Hayy, that is one of my concerns. The other thing is that a person should be absolutely sure before changing his religion. Imagine what it would be like for you to change your religion.” He laughed out loud at the absurdity of the answer. “Sikandar, that’s impossible! Islam is the true religion! It is the last revealed religion!” “Oh well,” I thought. I realized it was impossible to convey much of the post-modern relativistic sensibility to someone from a non-Western culture. This was especially true in this very static culture of rural Afghanistan, which was in some ways, perhaps, akin to the rigid Christian culture of the Middle Ages. Afghans couldn’t possibly be expected to know how experimental and open many Americans are to new ideas. They thought it was strange and interesting that I observed the fast of Ramadan while not being a Muslim. From my side, I doubted the sincerity of my interest in Islam. Was it truly profound? As I walked with Abdul Hayy, I told him about keeping the fast with my dear Afghan friend in California, Homayon Etemadi, who was also a famous Afghan miniaturist painter.  Homayon Etemadi “I had Homayon’s help. He advised me on how to carry out the fast properly. He was the most wonderful companion that I could have had for that experience.” “From what I have heard, the members of the king’s clan are not very good Muslims,” Abdul Hayy replied skeptically. “What relationship does he have to the king?” “He is King Zaher Shah’s cousin, Abdul Hayy, but I think he is a very good Muslim. Let me tell you more about him. Homayon once worked in the royal government as munshi, the Royal Secretary. He was also the Keeper of the Royal Library and the chief painter. He is a passionate hunter who used to travel with the royal hunting expeditions in the hills and marshes all over Afghanistan. I met him around 1987. My initial impression was of a modern, secular man. Since Homayon spoke no English, our first conversations were limited by my poor Persian. We immediately liked each other though. We soon met every week at his home, where we would talk for hours. This helped to advance my Persian quite rapidly.” As I described Homayon to Abdul Hayy, I remembered how this dignified older man would engage me in progressively deeper conversations about all aspects of Afghan culture. “From the very beginning,” I told Abdul Hayy, “it was clear to me that Homayon was meant to be my mentor. He groomed me in Afghan etiquette and language. He also taught me to paint miniatures in the old style of Herat. You see, Homayon had experienced other cultures. He had traveled and studied abroad. As secretary to the king, he met many dignitaries and was well-informed about the the ways of other countries.” “He does sound like a remarkable man.” Abdul Hayy said. “So how was it, passing the month of fasting with him?” “He was scrupulous about keeping the fast,” I answered. “On the days we were together, we rose well before dawn to take a small meal with water and juice. We passed the days absorbed in our work until the sun sank below the horizon, when we could again drink and eat. He kept his good humor and wore a lenient smile in the presence of those around us who were not able to keep the fast.” As Abdul Hayy and I walked in silence for a while, I relived some of my experiences with Homayon. I smiled as I recalled our first day of fasting. Once while traveling together during the fasting month, Homayon and I arrived in Pakistan from London, where we were guests at the home of one of Pakistan’s most famous calligraphers. When we arrived at his lovely home in Islamabad in the late morning, food and tea had already been laid out on the table. At first I thought that the food was meant for me, since I was an American and not Muslim. The calligrapher and his other guests were surprised to learn that I was fasting; they hesitated a few minutes, then went right for the food. “Not everyone can keep the fast, you know,” Homayon later said forgivingly, “some of them have medical problems or fly into a rage when they don’t eat.” I remembered how Homayon’s wife, Asifa, had recounted that she and her sisters would implore their father not to fast because he became so insufferable when he did. He would apparently stop fasting after a day or two. I considered how my own moods shifted more than usual. I also recalled seeing several fights on the streets of Peshawar during Ramadan. “After the first few days of fasting,” I rejoined Abdul Hayy, “a feeling of peace settled inside of me and I felt some spiritual benefit from it. I made it through the whole month without any great difficulty.” “You see, Sikandar,” Abdul Hayy said, “Islam is the true religion. Practices like fasting bring us closer to God. You have experienced the blessings of fasting. Sikandar, it seems that you are being drawn to Islam.” “I was experimenting, Abdul Hayy.” But he was right that I was thinking about Islam. Yet could I be true to the other Islamic precepts, I wondered, especially with such a different background, when I return to live in my own secular culture? Again I thought of Homayon; he was a good role model and I studied his approach. He practiced a quiet piety yet also blended easily into the modern world. It was true that he did not join in the congregational prayers at the mosque, nor banter in religious expressions of outward piety. He often voiced a concern about hypocrisy. I had certainly experienced many “religious” people, Muslim or otherwise, who were guilty of hypocrisy. Homayon never drank alcohol, despite the general acceptance of drinking among the elite of pre-war Kabul, but he never criticized anyone who did. He practiced kindness and spent most of his life expressing beauty in his paintings. As a thinker, he was strongly supportive of secular values, in particular of education. He was highly critical of the Islamist forces taking over Afghanistan. Whenever I would rejoice in Mujahideen victories in their struggle against the Marxists, he would say, “You don’t understand. The real fight has not yet begun. It will take place one day between the various ethnic groups and the ignorant religious organizations that have taken power in Afghanistan. That fight will go on for many years. People will use the name of Islam to pull our country into the depths of ignorance.” He was, as it turns out, correct in this assessment. I explained some of this to Abdul Hayy as we walked together. I knew that he could not possibly understand the pre-war culture of an Afghanistan that he was too young to remember. In just one generation, Afghanistan had been seized by the grip of religious fanaticism. I spoke to Abdul Hayy about the broad-mindedness of Muslims like Homayon. “Homayon and a few other educated Afghan friends of mine have a different view of Islam. They are not like these fanatics.” I described the broad vision of my educated friends, a vision that would undoubtedly be anathema to more literalist Muslims. I explained that my companionship with Homayon had drawn me closer to Islam. He had shown me an Islam that seemed more in keeping with the word’s fundamental meaning in Arabic, “surrender.” “You see, Abdul Hayy, I’ve observed some very fine qualities in Homayon. He is a clear thinker who likes to ask questions about what really motivates people. He is not convinced by an outward show of piety. As a Muslim, he bears life’s challenges patiently. He makes it his religious duty to be kind to those around him.” “He does sound like a good man,” Abdul Hayy replied. “In our culture, Sikandar, we are very respectful of our elders. They possess knowledge and experience. From your description of Homayon, I think that he must be a decent person, and I hear in your voice that you respect him very much.” Although Homayon was thirty years my senior, I never felt that the difference in our ages or cultures came between us. The Sufi poems I had memorized helped us to bond very quickly when we first met. Like many Afghans of an earlier generation, Homayon was strongly influenced by Sufism, the mystical side of Islam. He was surprised and amused to hear me recite, from memory, selections from the classics of Sufi literature—when I could not even carry on a conversation in Persian! Sufism had, in earlier centuries, absolutely dominated the literature of the region. Sufi poetry was widely memorized for its beauty and wisdom. Sufism is ecumenical in its outlook; it sees all religions as a means of recognizing one’s origin in a Divinity that transcends the religious formulations themselves. Homayon’s father, a Sufi poet who wrote under the name Farhat, had introduced him to a Sufi elite within the government of the old kingdom. Homayon told me many stories about these individuals. He also quoted the poets Bedil and Hafez frequently. “The Sufis penetrated to the core of Islam,” Homayon said. “Their realization of the true nature of things led them to understand that God is worshiped in every religion, by anyone who turns to Him with an open heart. The Sufis express themselves clearly in their poetry and other writings. These Afghan friends you’ve told me about are clearly not educated, so they can only harp on the most restrictive and limited doctrines of the Islamic faith.” Homayon was referring to the narrow-mindedness and lack of education that prevailed in the war zone. Most Afghans, including my companion Abdul Hayy, were illiterate. And in the changed wartime atmosphere of restrictive religious schooling, most would not subscribe to Homayon’s ecumenical views. The long war had stolen a whole generation’s chance at a basic education. The only education, if any, most of them received was elementary schooling and religious training. This meant memorizing Qur’anic verses and learning the basics of Islamic practice. Most Afghans that I met didn’t know what the Qur’anic verses actually meant, even though they could recite them in Arabic. The long days of slow walking and horseback riding with Abdul Hayy and the others allowed me a great deal of time to think about my own life. Why did I want to delve so deeply into such an alien culture? In some ways, I don’t think I could find a culture more at odds with the one I grew up in. Yet I often found common ground and a real joy in my Afghan companions. Afghans have a marvelous, often earthy sense of humor that is a pleasant relief from their own cultivated piety. I found that the average Afghan delights in a good joke and is happy to engage in punning. My friends would often laugh at the inadvertent sexual double-entendres they could make out of my innocent Persian. I found Mohammed Ali especially mischievous in this regard. His Uzbek eyes, set in a wide face, often betrayed his humor when I spoke. His natural curiosity about the world also led him to ask me about my own life. He was far more educated than the others in our group, so I had asked him to correct my Persian, and he was helpful in doing this, even though it put him in the awkward position of being both my teacher and assistant. Just before leaving on this trip, he had trapped me in a game of tomurgh. While we were feasting on a meat pilau, he gave me a serving that concealed the lamb’s kneecap: finding the meaty knee joint in one’s food is the start of this Uzbek game. I was then required to ask him what his challenge was. He said he wanted my Nikon camera with all of its lenses. I then stated my counter-challenge. I voiced my desire for a fine horse, a white stallion in fact. He accepted and the game was on. I had to keep the lamb’s kneecap on me at all times in case he asked for it. If he were to ask for it when it wasn’t on me, I’d have to forfeit the Nikon. My strategy was to try to deceive Mohammed Ali into asking for it from me while I held it concealed, in which case, I would win. He studied me closely all the time. I thought of how ridiculous it was to have become so preoccupied with this game of tomurgh while we traveled through a war zone. But maybe that was the point of the game. It certainly raised my attentiveness a notch—I was very attached to my Nikon camera.  A river valley in the Hazarajat We descended from the high mountain pass and hiked through the valleys of the Hazarajat. I was happily surprised to find that the Hazaras, who have Mongol features, took no notice of me at all. They seemed to have an attitude of “they all look alike” toward anyone not of Mongol blood. They had seen plenty of blue-eyed people from the north of their own region and probably thought I was one of those. This anonymity gave me the freedom I had hoped for to go about as I wished.  A samowar in the Hazarajat We stopped for a day at Bamian and I spent much of it under the great Buddha statue that I had always admired in photographs. It was truly immense. I imagined it painted and dressed in the gold leaf that once ornamented it. I pictured its original face, which for centuries had been cut away by the iconoclastic Muslim monarchs who conquered this region a thousand years earlier. I’m sure it would have been a calm, compassionate face inviting me to seek peace and serenity within myself. From Bamian we struck out on the road to Naiak. We traveled through wide, beautiful valleys cut by rivers and streams. These valleys were so idyllic and the weather so temperate at midday that I’d occasionally forget we were in a war zone and that danger might appear at any moment. Here and there farmers with oxen threshed wheat, circling over the stalks, trampling them to separate the grain from the chaff. At four thousand feet, wheat is harvested well into autumn. After some days of intense travel, I insisted we stop at some lovely rock pools to have a swim and bathe. With our game of tomurgh always in mind, this was my chance, I thought, to trick Mohammed Ali. I hung my long shirt on a tree branch with a small rock bulging in its pocket. With the lamb’s kneecap firmly under my tongue, I dove into the cool water wearing only baggy, pocketless Afghan trousers. Mohammed Ali eyed me suspiciously as he took notice of the shirt. “Sikandar!” he called to me, “How is the water?” He broke into a big laugh when I answered in a slurred, “It’s wonderful!” “You almost got me!” he laughed with the others. “You tricky man!” For the next few months we played this game, but aside from driving us crazy, it never came to a resolution. Mohammed Ali could be as serious as he was humorous. He was trained—a bit—in theology and was a fierce patriot who often extolled the bravery and sacrifice of the Afghan martyrs of the war. He would talk about the high-mindedness needed for the Afghans to overcome the Soviet invaders and the “godless Communists” who had taken over his country. He was far more curious than most of my companions about my background and personal life and he often asked me about life in America. I knew that there were limits about what I could explain to him about the radically different cultural atmosphere I grew up in. There was much in my upbringing that sustained me through the years in Afghanistan, but I could only share a small part of this with my Afghan friends. I had been raised in a politically liberal family of Democrats, and grown up between Tahiti and California. This unusual childhood in Tahiti had nurtured my deep love for nature and an innate trust in people. Growing up with Polynesians, I was comfortable with myself within nature, as a part of it. As children, we ran around almost naked, every day out swimming or playing on the beaches and in the rivers and forests. Tahiti was a place where the innocence of childhood was greeted by the innocence of an easy, happy culture that seemed to accept everything. The beauty of Tahiti’s pristine nature informed me about my own existence and reassured me about the coherence of life itself. I perceived this coherence in the myriad signs of nature. I saw her luminosity in the refracted sheets of sunlight criss-crossing the turquoise lagoons, mirrored in glistening seashells and sand. I smelled the earthy fragrances rising from the soil, spreading out in the humid air perfumed by flowers and vegetation. I listened to her voice in the birdsong spilling sweetly from Tahiti’s tropical trees and in the wind’s whispers and roars from their branches. But I was especially drawn to the beauty of the lagoon’s creatures where I saw perfection itself in their superb shapes and multi-colored designs. Their’s was a liquid world full of struggle and play, of symbiosis and survival. I never tired of watching the myriad varieties of these reef fish. Their stunning colors stood out all the more as they twisted and turned gracefully in and around the coral reef looking for a meal or parading before others of their species in elaborate courtship displays. All of this struck me as an eloquent communication, a stunning, visual lyricism. And in the background of this underwater scene was a tangible presence, an aware silence that I sensed permeating the lagoon. I went snorkling every day to explore this world that immediately made me feel a part of itself. These daily perceptions of nature were mirrored in my imagination and in my dreams. The self-evident rightness of this world made me feel the rightness of my own nature. In stark contrast to my Tahitian childhood, I thought that Afghans did not seem at ease with their earthly nature. “Rather they are uncomfortable with their nature,” I mused when considering the burqa (the head-to-toe veil that women wore outside of their homes) or the way men kept their bodies fully covered even in the heat. In Afghanistan, I was reminded of the adjustments I had had to make when my family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1964, when I was a formative thirteen. I was shocked by the more ordered but less harmonious environment. My childhood sensibilities had to give way to the norms of my new culture. I was suddenly in a society that was preoccupied with itself and the many changes occurring in the 1960s. I grew up struggling over the meaning of life during the strife-ridden Vietnam era. The undeveloped Tahiti of my early years possessed a beauty that was always at the center of my experience. As a child I felt deeply that God was present in the beauty all around me. The fact that I had been baptised Catholic did not really seem to contradict my child’s worldview, thanks to the lenient, open-minded attitudes of my family. My parents, though privately religious, didn’t go to church and never harped on sin and hellfire. In Tahiti, I rode my bicycle to various churches near our home in Punaauia, to enjoy the Mass that was celebrated for the most part through congregational singing. They sang the himenes, the Polynesian pronunciation of “hymns” in a manner so glorious and joyful that I was sometimes brought to tears. It wasn’t until I was ten or so that I first heard of “original sin” and the idea that God had come to earth as a man to be sacrificed for our sins. As a teenager in a Catholic high school, I struggled with these doctrines of Christianity because I found them alienating and hard to reconcile with my innate spirituality. The evident authenticity of nature stood out for me as the most clear divine revelation, as a ruthless touchstone for assessing human doctrines and worship. I couldn’t help but notice a number of my Catholic friends behaving inauthentically, especially around parents and clergy. It seemed that attending church was really about cultivating a religious persona that was not true to human nature. Hypocrisy was the outcome of peoples’ attempts to deny or subdue their human nature. In Afghanistan, I felt I was seeing the same dynamic in Islamic culture: the cultivation of religious personas, denial of human nature, and the resultant hypocrisy. Both Christianity and Islam came from the same Semitic source. They both seemed fundamentally world-denying with a view to an eternal afterlife that required transcending one’s attachment to an “impure” world. On one hand I was still guided by the spirituality I witnessed in nature and the universe around me. On the other hand I was drawn to an archaic religion that had even more rules to follow than the Catholicism of my childhood. How is it, I thought, that I was so drawn to Islam? I remembered first reading the Qur’an in my teens. I was struck by the beauty of many of its verses, but put off by other passages that featured the same vengeful anthropomorphic God that had cooled me to Christianity. I was surprised to find myself coming back to the Qur’an repeatedly, despite those feelings. I reminded myself that it was part of my research, part of my need to know everything about the people I was working with. But in truth, I was drawn to the undeniable beauty in the revelation, especially as I learned enough Arabic to understand it and to hear it in the original language. When I first studied Sufism in the 1970s, I had learned a number of translated verses from the Qur’an, verses that were at the core of its spiritual message. These were still the passages that most appealed to me. To Allah belongs the East and the West. Whichever way you turn, there is the face of Allah. Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth. The similitude of His light is of a niche containing a lamp, the lamp sheltered in a glass. The glass shines like a luminous star. It is fueled by the oil of a blessed olive tree neither of the East nor the West, the oil itself luminous though no fire touch it. Light upon light! I struggled with other passages about hellfire and punishment, and with verses that seemed to relate to the archaic organization of the desert society that the Prophet Muhammad grew up in. It was a particularly strict interpretation of these latter verses by the members of the various fanatical Islamic organizations in Afghanistan that caused such oppression and suffering. Yet every chapter of the Qur’an begins with God’s names Rahman and Rahim, meaning “Compassionate” and “Merciful.” Somehow, the dehumanizing stresses of war had muted Islam’s ample, clear message of mercy, justice, and humanity. I wondered, not for the first time, where I was going with all of this. How could I possibly consider converting to Islam while I was still so ambivalent? I wondered how I would be able to abide by the Sharia, Islam’s code of behavior, after decades living a secular Western life and without much faith in the redemptive value of rules. It was not until years later, after much study and practice in the spiritual path of Sufism, that I came to understand that this exquisite, pristine nature that had surrounded me in childhood could be apprehended as a spiritual force within my own heart and mind. It was only then that I was able to respect the role and practice and mission of all religions. I saw that they were all engaged in refining the inner gaze through devotion and selflessness, to allow for the witnessing of this peerless beauty. Then, after decades of observing and finally understanding the disorganization and selfishness within myself and others, I accepted the purpose of religious and moral injunctions. In the meantime, I could only be patient with my doubts and continue to study Persian and to memorize poetry as we trekked our way into the remote regions of the north of Afghanistan. After two weeks of walking and riding, after many adventures, we descended the northern face of the Turkestan mountain range into Faryab province. Traveling through forests of walnut, here and there sprayed by the mist of waterfalls, we made our way to the valley floor and on to the town of Gurziwan. My Uzbek companions began singing emotionally about their beloved Faryab. I realized how much everyone yearns to get home. Their sad song reminded me that I could not be farther from my own home. Not only was I thousands of miles away, I felt as though I had entered a world living centuries in the past.  Commander Turan Sayid Akbar Our first official stop was to see the famous local commander, Turan Sayid Akbar. He was a wizened Tajik leader affiliated with Jamiat Islami. Turan Sayid greeted us warmly and offered us a day of wonderful hospitality before revealing his anxiety about the recent events taking place in the area. His territory was under siege by the Hesbi Islami commander, Nasim, an Uzbek operating from the large town of Darzab over the next mountain. Recent fighting had been fierce and people were being taken down by snipers in the hills. I was devastated when Mohammed Ali announced after this meeting that we could not continue on our planned route because of the danger posed by Hesbi Islami. “We’ll have to return, Sikandar. It’s too dangerous. You might be captured or killed and it’s also dangerous for me because of my family.” Mohammed Ali was referring to the influence of his famous brother, the poet Abdul Ahad Tarshi. Abdul Ahad was an Uzbek voice in the predominately Tajik Jamiat Islami that had strongly criticized the northern commanders engaged in interethnic war. On this journey I observed more fighting between rival groups of Mujahideen than with the Marxists. Again, it seemed that hypocrisy was showing its devious face, this time over power. While the popular myth was of a noble jihad against a godless regime, often the actuality of war in Afghanistan was interethnic fighting and power-grabbing by violent individuals.  Children of Gurziwan  A village near Gurziwan We stayed in Gurziwan for several days. Mohammed Ali’s family lived there, so we spent much of our time visiting them. We caught up on sleep and ate well. Although this was pleasant enough, I was upset at the prospect of turning back and I also felt a bit duped. It seemed that our journey north had been orchestrated, in part, to allow Mohammed Ali and his relatives, Asadullah and Abdul Hayy, to visit home. Our foundation’s plans involved making a large circular trip that would have included meeting with many of the needy communities throughout the north to assess how to share the funds we had left in safekeeping with Commander Nurullah. I argued, without success, that we should continue and negotiate our passage beyond the danger zone. Mohammed Ali was adamant that we could not go farther. After several days, I stubbornly announced that I would go forward on my own. “You will be killed, Sikandar! Don’t be crazy. You don’t know what these people will do to you!” he warned me. I tried to persuade him. “We must go, Mohammed Ali. We haven’t come all this way just to turn around! I am responsible to the agencies that have entrusted us with their money. If you won’t go, then I must go on.” “Sikandar! Don’t do this. I won’t be able to help you if you’re captured.” “I’ve made up my mind,” I answered. “I will go on, whatever comes of it.” After a couple days of confusion, Abdul Hayy again came through for me, by weighing in on my side during another deadlocked meeting. “I will go with Sikandar. I cannot let him go on his own.” He was far younger and less powerful than Mohammed Ali, but he was courageous. He possessed a strong conscience as well. I accepted his companionship gladly. Mohammed Ali sulked quietly up to the day of our departure. That day we made peace and agreed to meet up later, at Teri Mangal on the Afghan border. Abdul Hayy and I left the safety of Gurziwan and made our way on horseback up the mountains to the north. In the cool morning of our departure, the thought occurred to me that I may be riding toward my own death. Abdul Hayy seemed sluggish as our horses struggled with the steep trail winding up the foothills. By afternoon when we reached a mountain crest, he was feverish. I began to worry as his strength failed him. He was barely able to sit upright in the saddle as we descended the northern slope; we rode toward a farmer’s humble dwelling by a creek in the valley below. Abdul Hayy spoke for a few minutes with the farmer, a wonderfully simple man who immediately took us in. His family provided us with tea and meager food. I came to the conclusion that Abdul Hayy was suffering from malaria, which is rampant in much of Afghanistan, so I started him on the anti-malarial medicine that I carried with me. With the meal and a good night’s rest, we were able to continue on to Belcheragh the next day. Abdul Hayy was weak but able to travel along slowly. As we arrived at the town center, there was an uproar and we were immediately swarmed by at least two dozen warriors carrying AK-47s and glaring at us. After ushering us inside their headquarters, they questioned us, threateningly, in their heavily-accented Persian. I recognized them by their Mongol facial features and dress as Turkoman. They were stiff and reserved as they conversed with us. I had already decided to accept whatever would befall me in order to accomplish my mission. When I explained that I was a foreigner, I could see a couple of them becoming angry. It was a difficult moment.  Abdul Hayy on left of Turkoman fighters “Noble fighters,” I said. “Thank you for welcoming us in. May you live long! I have just recently come from Turkey, where I met with my friend Abdul Karim Makhdum.” At these words they all looked closely at me. “You have seen Abdul Karim Makhdum?” Their commander, Juma, immediately asked. “Yes, I’ve just a couple of months ago visited him at his home near Tokat—a home he’s recently built,” I said, adding many other details about him and his current life. Abdul Hayy looked at the fighters’ now joyful faces and turned to me in utter surprise. He smiled as I continued to speak about Abdul Karim. I explained that I had met the famous exiled Turkoman leader in 1985 when I traveled through Turkey. Our foundation had helped his people there, some of them relatives of the fighters we now sat with, by introducing small income-generating projects. We had operated a leather jacket sewing and rug-weaving project there for several years.  The proud, fierce Turkoman of Belcheragh Abdul Karim hadn’t seen his native Afghanistan for years and the Turkoman warriors sitting before us only knew what they heard from occasional travelers. Their suspicions became joy at meeting me and this led to a feast. We spent much of that night enjoying each other’s company. Finally, late in the night, I set up my tent inside of the large mud house. It only took me about five minutes to set up the tent, and the speed of this amazed them. Each man wanted a turn to sit with me inside my tent. Some of the fiercest fighters in the whole area were suddenly behaving like happy children. I knew that my path had been opened by the grace of providence. The next day, Commander Juma accompanied us to Darzab to introduce me to “Engineer” Nasim, the Hesbi Islami commander of the region. (Important people in Afghanistan are often given names like “doctor” and “engineer,” regardless of their qualification for the title.) Commander Nasim wasn’t there, he had gone off to battle, probably with my new Uzbek friend Turan Sayid, I mused sadly. Commander Nasim’s brother, Ustad Rahimi, offered us a warm welcome. I presented the letter of introduction written by Wardak’s Commander Asif. Ustad Rahimi read it, then looked up and asked me to recount my journey and explain my reasons for coming to northern Afghanistan. After consulting with his advisors, he accepted my plan to help the internally displaced refugees of the region. As I prepared to sleep in the private guest quarters, I remembered the stories I had heard about the people of Darzab—that they offer hospitality and lodging readily, then when you’re sound asleep, someone crushes your head with a heavy stone. Getting to know myself better on this journey, I was surprised to find that I wasn’t easily swayed by threats of violence, or even, as in this case, tales of it that could yet be true. I peered into my conscience to carefully examine this bravery, and concluded that I didn’t, in fact, possess the bravery that I had read or heard about, the bravery of myth. Rather I found that I had rediscovered a kind of deep trust in the rightness of things. It was really a trust that things need to be what they are, and this included my own life and my future. I suppose I came to the realization that I was a fatalist, but in the most optimistic sense of the word. That night I fell easily into a deep sleep. When we met the next morning, Ustad Rahimi asked me how long I planned to be in the area. Apparently there were bombing raids taking place near headquarters; he asked me if I was interested in witnessing these. Of course, I agreed to go with him. We traveled the area looking at the results of recent bombings. Later in the day I heard the rumblings of distant explosions as I studied the sky. High up beyond the reach of the recently distributed American Stinger missiles, the planes came into view. Moments later there were more rumblings, closer this time. Soon the aircraft flew northward in the direction of the Soviet Union.

|

| Site Designed by James Dilworth | © Robert Abdul Hayy Darr, 2006 |